Staff field report on visit to World Health Partners, new winner of the Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship

Our team bounced along the dirt road in Samistipur district in rural Bihar, India, who knows how far from the nearest paved road, until we finally arrived at the beautiful and peaceful village of Akha. In rural Bihar you may be far from a paved road, but you are never far from people—the state is 2/3 the size of California, with three times the population. Almost all of Bihar’s very few doctors live in cities, and the majority in the capital of Patna. Over 70 million people live in Bihar’s villages, far from any city, and hence far from any doctor. Villagers typically only make the long arduous trip to a city to see a doctor in extreme cases. As expected, this lack of available doctors has led to unaccredited health practitioners filling the void, responding to the demand in almost every village. These rural health providers typically have some limited medical experience but no formal training.

We entered a small brick room with no embellishments, nestled among thatched roof and dirt walled houses and dung patties drying in the hot sun. Inside we met Hardener Sharma, the village health provider, a young man who had recently joined the World Health Partners network. Prior to joining the network his only training was having worked as an assistant to a doctor in a city a few hours away. He was excited to share how the World Health Partner network had improved the quality of care he provides. The room was small and spartan but clean, with a bed, a tiny wooden table and a few chairs. On the table was his “doctor” bag and a cell phone. An older woman with hardened features and a crying baby on her lap sat next to him with a worried expression. Hardener reassured her and called a number on his cellphone, and then hung up. Two minutes later his phone rang and a World Health Partner counselor, similar to a physician’s assistant, took down details about the woman and her baby, and then put Hardener on hold. A minute later Hardener greeted a doctor on the other end, explained a few details, and then passed the phone to the woman who conversed with the doctor. Hardener then spoke briefly with the doctor again, and the woman seemed relieved, even gracing us with a heartfelt smile. A few minutes later a text arrived on Hardener’s phone—a prescription from the doctor for medicines for the baby.

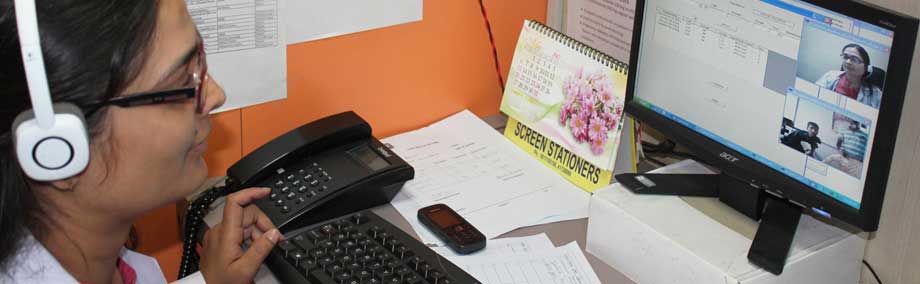

This exchange is at the heart of World Health Partners’ model—improving the quality of care of rural health providers in rural Bihar. We witnessed many more exchanges, some of them using World Health Partners’ telemedicine system whereby rural providers connect to doctors via videoconference and use medical devices connected to a computer that allow doctors to listen to a stethoscope, check pulse and blood pressure, and even perform ECGs. World Health Partners is soon rolling out a new telemedicine device that will work over cellphone networks without a broadband connection, allowing people like Hardener to provide accurate readings and vitals to the doctors he connects patients with.

The next person Hardener introduced us to was a woman in her twenties, quiet yet confident. She did not seem sick at all. She explained how she lived in a nearby village, and had come down with Tuberculosis. Weak and despondent after visiting two different “doctors” (informal village health providers) who could not cure her, she had decided to return to her parents’ village to see Hardener. With the help of a doctor reached remotely by cellphone, she was referred to a clinic where she could be properly diagnosed for TB and given a prescription for treatment. Only qualified providers may administer the treatment, a training World Health Partners provides to all providers in its Bihar network. Hardener is now administering the complete DOTS treatment following standard protocol, with doses every few days recorded diligently on the government issued record sheet. Adhering to the treatment plan is important not only for the woman, but also so that the strain of TB does not develop resistance to the treatment. The woman is staying with her parents in the village throughout the treatment period even though she clearly is feeling much better and stronger since the treatment began. And because practitioners are part of the villages they serve and in close proximity to their patients, it is easier for patients to adhere to the stringent TB protocol which requires diligent administration of treatment by a certified provider every few days.

In addition to understanding more deeply the low standard of rural health care in most of Bihar’s 40,000 plus villages, we also appreciated connecting with the World Health Partners staff and having long talks about how they are adjusting the model, monitoring, learning and fine-tuning it as they expand it throughout the state. Learning about rural health care through their lens was powerful and exhilarating.

By experiencing the remoteness of the villages in which World Health Partners operates and seeing the model in action, we gained a deeper understanding of the World Heath Partners model and how each piece of it works, and were able to ask more probing questions that shaped a significantly different understanding of the impact than we previously had understood. Telephone calls and written documents prepared us well, but nothing compares to seeing the model in person and talking to the actual providers. We leave with a truer, firsthand understanding of the innovation and impact, along with stronger relationships with the social entrepreneur and key staff.