When Dr Olukayode Oguntimehin saw the news of Nigeria’s first case of Covid-19, there was no dread. If anything, it was a familiar tingle of the strenuous work the fight ahead would require and the belief in the people who would lead the battle.

Eight years ago, he had been on the frontlines himself when an infected airline passenger disregarded warning signs and arrived in Nigeria with the ebola disease.

Dr Olukayode served as the Ebola Incident Manager for Lagos State, Nigeria, a crisis extension of his role as Permanent Secretary of the Lagos State Healthcare Board. In this role, he led a team of trained medical workers with a mandate to identify hotspots in communities and educate residents on appropriate measures with the aim of reducing transmissions.

At that moment, he was counting on the systems designed eight years ago to kick in. He was confident that a recall of important behavior change programs during Ebola would result in an eagerness to embrace protective measures.

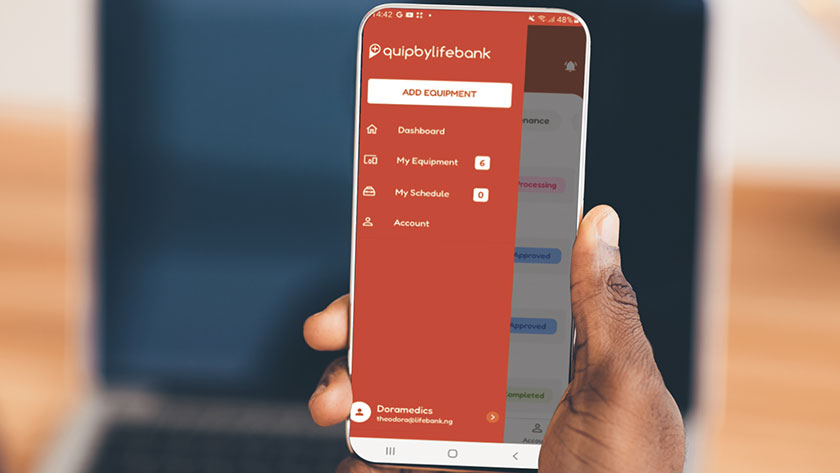

In Abuja, Nigeria, Sodiq Oloko, Director of Operations at LifeBank was finishing a presentation to stakeholders. LifeBank is a healthtech building a safe supply system for hospitals by enabling them to order blood, oxygen, and medical consumables in seconds. A persistent phone call cut his presentation short.

Founded in 2016, LifeBank uses technology and innovation to provide access to critical medical supplies to hospitals. The lack of access to medical supplies across the African continent is responsible for wide-ranging health problems.

Postpartum hemorrhage causes 24 percent of Nigeria’s maternal mortality (814 deaths per 100,000 live births: WHO, 2017). Severe pneumonia causes critically low oxygen levels and adversely impacts 4.2 million children every year (UNICEF, 2020).

LifeBank currently operates in Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia serving 1,700 hospitals and delivering over 170,000 products on time and in the right condition. The result is over 50,000 lives saved and health sectors strengthened.

Sodiq’s presentation was intended to get stakeholders with a presence in Kano, Northern Nigeria to commit to supporting LifeBank’s expansion to Kano.

The call was from his CEO, Temie Giwa Tubosun. The news was brief and packed a punch. The first case of Covid-19 had been confirmed. It was time to put an abrupt pause on expansion plans and return home to prepare for the battle to come.

Unlike Dr Olukayode Oguntimehin, Sodiq Oloko did not have the hindsight and experience of the fight against Ebola to draw on.

For him and the 100+ healthtechs in the country, this was a call to arms.

In Lagos, Nigeria, the epicentre of the virus, Nurse Hauwa Ajagbe was pulled out of her facility to join a deployment of nurses at the special Covid centre at the Mainland Hospital, Yaba.

She reflects on the months that followed the announcement of Nigeria’s first case and the struggle of hundreds of other nurses.

“Covid was draining and took a toll on our mental health. At first, patients were asymptomatic and very active when I was drafted to the Covid special center in April,” said Ajagbe. “From May things took a turn for the worse. Community transmission was in full force and patients came in with very life-threatening symptoms and a need for oxygen”

In the midst of such troubling circumstances, why should healthtechs think about expansion and how do they navigate crises ensuring that they drive growth and build their relevance?

The easy answer is that in times of crisis, governments and key stakeholders turn to players in the health sector with a track record of innovation that tackles complex problems. There is also an openness to new ideas, experiments, and last mile initiatives that can bring support.

The hard answer is how to consciously do this when there are competing concerns, government policies that stifle growth, and rising death tolls.

The market and need for innovation is obvious. In its coverage of African healthtechs, TechCabal reports that data from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that even though Africa carries 25 percent of the world’s disease burden, its share of global health expenditures is less than 1% percent. But it gets worse—the continent manufactures less than 2 percent of the medicine it markets and sells to healthcare facilities, hospitals, and pharmacies.

In this case study, we turn to the key actors in LifeBank’s story of expansion and growth despite a major crisis. They provide insight and examples of how African healthtechs can navigate crises and turn uncertainty into the seeds for expansion.

Temie Giwa Tubosun– CEO and Founder, LifeBank

Ayo-Olufemi Michael– Director of Technology and Innovation, LifeBank

Sodiq Oloko– Director of Operations, LifeBank

Aisha Abiola– Chief of Staff, LifeBank

For Sodiq Oloko, the flight back to Lagos provided time to think about the hard questions- how do you respond to a health crisis with no prior roadmap? How do you continue to run sustainably?

Once he landed in Lagos, he headed into a meeting with LifeBank’s founder and CEO, Temie Giwa Tubosun. The meeting ended with two major pillars that would guide LifeBank’s actions. These two decisions were critical in LifeBank’s response and growth during the Covid-19 crisis.

Prepare for different scenarios: At the onset of the pandemic, a lot of time was dedicated to making sustainability plans. The possibilities of a lockdown were considered and all LifeBank offices at that time ( Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt) were turned into residential living areas to allow staff to work without restrictions. This early decision meant that when nationwide lockdowns were announced weeks later, LifeBank had already transitioned to a residential workflow that ensured that the team continued to work without restrictions.

Start building a response: Crisis requires an innovation-first culture. This allows you to be perceived as a forward-thinking organization that has the capacity to provide leadership. The trust that your initial innovative efforts yield is critical for getting support from private and public partners.

Putting this to practice, Sodiq notes:

“For LifeBank, the early weeks of the pandemic saw us go into brainstorming mode. This provided an understanding of the immediate problems the pandemic presented;

These insights resulted in the introduction of a hand washing app called Safe Hands, the production of social distancing materials called Safer Circles, and entering into talks with the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research about how to scale free testing across Nigeria.”

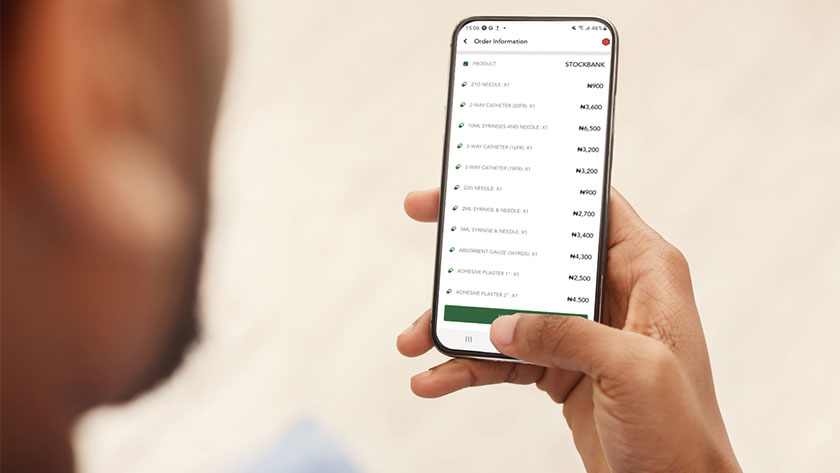

As a result, LifeBank developed Covid-19 saliva sample collection kits that provided testing for 17,000 frontline health workers, onboarded 64 biomedical engineers to repair equipment, and enabled 340 hospitals to access quality medical supplies via medical consumables supply product StockBank.

During the onset of Covid-19 and in the months after, expansion of any kind was the most unlikely strategy in a crisis with no roadmap or blueprint. In that same period, LifeBank expanded to Kenya and Ethiopia. It also gradually expanded its presence in Nigeria from three cities to nine.

How does a healthtech company extend its presence to a new country when borders are closed and regulations are stifling? In times of crisis or business as usual, the rules of engagement are the same, according to the LifeBank team.

Reflecting on the expansion process, Temie notes that the severity of the Covid-19 crisis was an important motivation in LifeBank’s expansion drive.

“The plan to expand predated Covid-19 but Covid accelerated it because it showed us the potential for the work we do, how far our impact could go,” said Temie. “Before Covid, it had been a while since I came face to face with the impact of our work. Covid made us realize the consequences of LifeBank being big and present. It validated our model.”

Expansion requires careful planning, research, and a healthy dose of resilience.

Determine need in the new location: The viability of a proposed location can be assessed through research if there is publicly available and verifiable data but assessment should never stop there. Visitation to proposed expansion locations can help you decide if there is a demand and if that demand justifies an expansion. It is also an opportunity to determine if the number of customers in the location support business growth or the development of new products.

Determine supply: The twin concern after establishing the presence of a need/demand is to figure out if supply is consistent and what factors control supply. If supply is insufficient, it is a primer for conversations around backward integration. How can you build a supply system? What partnerships can ensure constant supply?

Regulations & policies: What regulations or policies affect the industry? Are they local to it? What requirements will we have to meet or restructure our business to ensure compliance? It is very helpful to comprehensively analyze regulatory concerns in partnership with business and compliance advisers familiar with local laws and the sector.

Leverage local stakeholders: In the case of LifeBank, our primary stakeholders are blood banks and hospitals. Before actually setting up shop in a new city or country, it is important to pay intermittent visits. These visits allow you to meet key stakeholders, understand the business culture, and get a sense of prevailing regulations.

Government partnerships: Working with government institutions with a national/ regional presence often means that you are never starting from scratch. You can count on them to make introductions across sub-national levels. For LifeBank, The Nigerian Institute for Medical Research provided mobility and regulatory support to help us set up operations in Kano during the peak of Covid-19.

Joint initiatives: A crisis can become an enabling environment for very fast-paced and productive private-public partnerships. Dedicate resources to build a relationship with public sector officials who are very open to ideas and innovation at that moment. If you have a pre-existing culture of innovation, you will find partners who trust your track record and are willing to trust you enough to partner in key initiatives.

LifeBank’s Director of Technology and Innovation, Ayo Olufemi-Michael has heard the words; “We are expanding to a new country ” define his quarterly goals frequently. From a technology standpoint, he explores what considerations healthtechs should be evaluating.

“During the pandemic, we had to do a lot of changes to respond to what the pandemic market was saying but my role has always been the same. Making sure we get to market as soon as possible.”

Language barrier: A tough question to answer is how to customize a product to fit a new context and language. When we were expanding to Ethiopia, we tried and failed to use a mobile translator for the copy on our app. It did not work because a lot of context was missing. We had to delay the launch to sit down with a linguist who translated our interface to fit the language, culture, and context of our new location.

Technology penetration: You have to consider very carefully the level of technology acceptance and penetration in the different expansion locations. Different countries or cities rely on standard systems.

Not taking that into consideration can mean releasing a product that is dead on arrival because it is out of touch with the realities of the people you designed it for. For example, when we launched in Kenya, we quickly discovered that the mapping system we had designed for our product could not function in Kenya because it had a different mapping system. This required us to go back to the drawing board to design a system that worked for Kenya.

Costly mistakes like this can be avoided by researching your sector to discover the systems being utilized by other startups. If there is no pre-existing system, then you must be ready to build by communicating with partners and customers to understand their problems and needs.

LifeBank’s Director of Technology and Innovation, Ayo Olufemi-Michael has heard the words; “We are expanding to a new country ” define his quarterly goals frequently. From a technology standpoint, he explores what considerations healthtechs should be evaluating.

“During the pandemic, we had to do a lot of changes to respond to what the pandemic market was saying but my role has always been the same. Making sure we get to market as soon as possible.”

Language barrier: A tough question to answer is how to customize a product to fit a new context and language. When we were expanding to Ethiopia, we tried and failed to use a mobile translator for the copy on our app. It did not work because a lot of context was missing. We had to delay the launch to sit down with a linguist who translated our interface to fit the language, culture, and context of our new location.

Technology penetration: You have to consider very carefully the level of technology acceptance and penetration in the different expansion locations. Different countries or cities rely on standard systems.

Not taking that into consideration can mean releasing a product that is dead on arrival because it is out of touch with the realities of the people you designed it for. For example, when we launched in Kenya, we quickly discovered that the mapping system we had designed for our product could not function in Kenya because it had a different mapping system. This required us to go back to the drawing board to design a system that worked for Kenya.

Costly mistakes like this can be avoided by researching your sector to discover the systems being utilized by other startups. If there is no pre-existing system, then you must be ready to build by communicating with partners and customers to understand their problems and needs.

“Remember that you can never just copy and paste code,” said Olufemi-Michael. “You must research to establish user behavior and the opportunities it presents.”

The bright lights of a new facility or speeches from dignitaries can mask the challenges that it takes to achieve a successful expansion. Aisha Abiola, Chief of Staff at LifeBank explores the challenges from a strategic point of view covering people, product and growth.

Sodiq Oloko pitches in with regulatory challenges and other teething problems that occur when startups find new homes.

Hiring: Getting early believers when you move into a new location is hard. When we expanded to Kenya, we had to depend on a team that we recruited 100 percent online. Luckily for us, this worked out well. For new cities in countries where we already have a presence, hiring and creating new teams is easier. This is because we already have a culture of preparing team members to lead expansion efforts and set up new teams. This kind of training and culture fuels growth.

With ample experience of how much can get lost when trying to communicate with someone from a different culture, Aisha notes the criteria for picking leaders in new countries.

“For new countries, it is important to focus on finding people who are entrepreneurial, committed and can explain things clearly navigating the difference in cultural contexts with ease,” said Aisha.

Building Trust: Getting suppliers and customers to trust you enough in a new market can be very difficult. A strategy that often works is to pitch extensively to every interested partner/ customer. Focus on the most interested partners and work with them for an extended period. You can then leverage your work with them to attract a bigger customer and partner base.

Regulations: If you stick around long enough, you will find yourself combating an adverse regulatory change in a current market or having to adjust to regulations in a new market.

This is why it is very important to have an open line of communication with government partners and stakeholders. When we began operations in Port Harcourt, south of Nigeria, we found out that the government had banned the use of motorbikes across the state.

For us, bikes represent a very effective way of getting medical supplies quickly to hospitals in the right condition. Owning our fleet of bikes also meant we were able to cut out the inefficiencies and uncertainties of a public transport network. Being unable to operate with bikes would be a fatal blow for our business in the state.

We were able to pitch LifeBank for an exemption permit by clearly outlining the impact of our work in other markets and how the use of bikes is critical to provide that same level of stability and quality to the people of Port Harcourt. Again, a network of government institutions and major private operators were critical because they validated the claims we made and they also vouched for our track record as a business.

Years of navigating government and private stakeholder relationships have left Sodiq certain that startups should ensure that they have a designated employee for this function.

“For young healthtechs, it is critical to build out the government and partnerships function in your team as early as possible. While you may not hire specifically for it at an early stage, it should be a function assigned to a team member or co-founder who can pitch, negotiate, and navigate relationships easily. It is an important investment that will continue to yield returns as the business expands.”

Healthtech is a nascent space and converting a deeply traditional sector can be incredibly hard, but there is a massive opportunity to build smart, sustainable businesses.

According to investment data by Briter Bridges, African health startups and biotech startups raised $392 million in funding in 2021—an 81 percent increase from 2020’s $110 million which was the year with the highest in health tech history on the continent.

The absence of critical infrastructure to solve paper and pen data storage, inadequate medical equipment and funding, inefficient drug supply chains, and last-mile health service delivery presents a huge opportunity for African healthtechs Over the next decade, more healthtechs will emerge to plug these gaps and build sustainable businesses. It will be a game of continuous integration, partnerships and continuous development but the future is bright.

A few years shy of clocking a decade running LifeBank, Teme Giwa- Tubosun’s words to other healthtech founders across the continent captures the spirit, resilience and courage that the sector requires.

“You have to believe in your purpose and keep the faith. A lot of people are going to doubt the business model, they will question your market size. It may take long, but you are going to build a giant sustainable business.”