Skoll World Forum Interviews: Spotlight on Youth Climate Coalitions for COP29

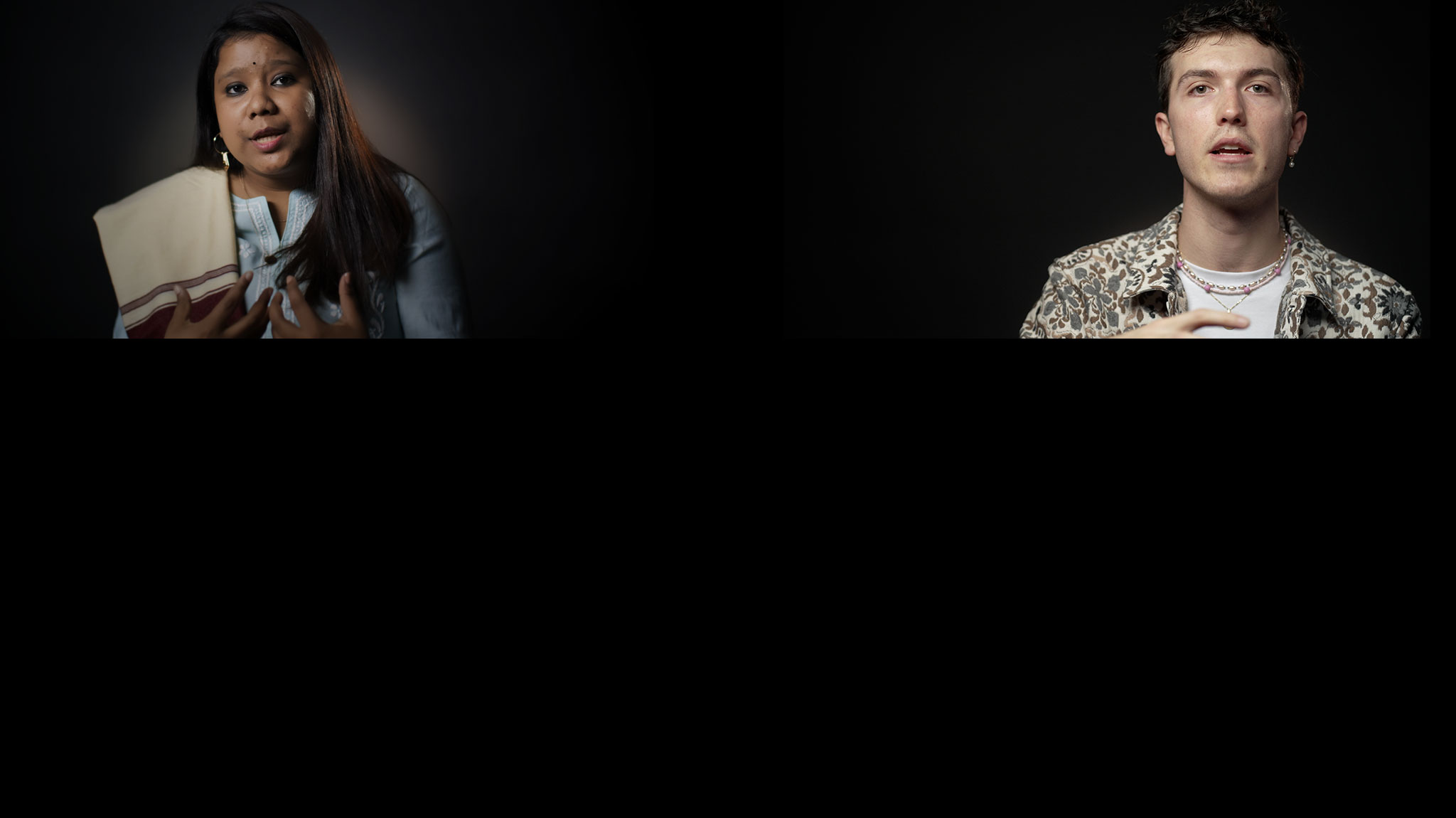

By Archana Soreng - United Nations SG Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change 2020 - 2023, By Nathan Méténier - Youth Climate Justice Fund

As national and international decision-makers converge in Azerbaijan this week for the UN Climate Change Conference (COP29), many of our partners around the world are doubling down on efforts to make the case that the most effective climate solutions are those driven by communities closest to the challenge. From Latin America to Africa to South Asia, those communities include youth and Indigenous Peoples.

Skoll Fellow Archana Soreng, who participated in the UN Secretary-General’s Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change from 2020 and 2023, is committed to reclaiming spaces for young people and Indigenous communities to engage in climate policy decision-making. A member of India’s Khadia tribe, Archana is a researcher and advocate focused on climate justice, biodiversity conservation, and Indigenous rights in India.

Nathan Méténier is another young leader approaching the work with an intersectional lens. A climate, youth, and LGBTQI+ activist, Nathan focuses on building youth-led movements. Not only do young people have the potential to help reverse the climate crisis, they are also the faces of the transition to greener economies and care deeply about their own workforce readiness for clean, sustainable jobs.

Watch the videos or read the full transcripts below to learn more about these inspiring young activists and their vision for a clean, green future for themselves and their peers.

Archana Soreng belongs to Khadia Tribe from India. She is the Former Member of the First United Nations Secretary General’s Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change 2020-2023. She is a Climate Justice Advocate working on reclaiming spaces and amplifying the Perspective of Indigenous Community in the Climate Justice Discourse. As a Young Indigenous Women, she has been working across Global, Regional and National Level on Connecting Indigenous Youth, Research and Documentation on the Indigenous Knowledge and practices with respect to Climate Justice , Climate Action and Biodiversity Conservation. She has been working on Climate Justice with an Intersectionality of Land and Forest Rights of Indigenous Peoples. She is also working on making sure that Climate Finance and Climate Philanthropy is accessible to Young people and Indigenous Peoples

Nathan Metenier is a 24-year-old climate justice & LGBTQI2S+ advocate. He is the co-Director of the Youth Climate Justice Fund, the largest youth-to-youth participative fund on climate and environmental issues. Nathan served as the youth advisor to Antonio Guterres’ Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change from 2020-2023. He founded Generation Climate Europe – the largest coalition of youth-led networks on climate and environmental issues at the European level. Nathan was also the co-chair of the youth pre-COP26 and is a former Board member of the European Environmental Bureau and Youth and Environment Europe. He seats on the Advisory Board of the Goals House and the young leaders forums of both IKEA and Ørsted. He is also a 776 Foundation fellow awardee. In 2020, he was nominated with 5 other young European for the “Young European of the Year 2020” award. He graduated from Sciences Po in France and has a MA in environmental policy and regulation from the London School of Economic

- Check out our complete interviews below with the community members featured above as part of our Role Models For Change podcast series below

- Click to learn more about The Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change

- Click to learn more about Youth Climate Justice Fund/a>

Announcer (00:02):

Welcome to Role Models for Change, a series of conversations with social entrepreneurs and other innovators working on the front lines of some of the world’s most pressing problems.

Archana Soreng (00:13):

Johar. My name is Archana Soreng. I belong to Kharia Tribe from India. And I am a researcher working on rights of indigenous people, climate justice, and biodiversity conservation. I also identify myself as youth climate justice advocate, and advocating for young people, indigenous people in the climate justice space.

(00:42):

And off late last year, we curated climate justice fund, youth climate justice fund. And I’m also part of the steering committee.

Matthew Beighley (00:54):

So just to say I don’t know what climate justice is, can you tell me what is climate justice?

Archana Soreng (00:59):

For me, climate justice is about reclaiming spaces for indigenous people and young people in the climate discussions. It’s also how do we make sure that indigenous people and young people are having a seat at the table in the climate decision-making processes because the laws and policies are impacting us. The climate crisis is impacting us, and our voices need to be part of the law making, policymaking. And most importantly I feel when I talk about climate justice, it’s also how do we make sure that we undo the injustices done to the indigenous people and young people over the years through the climate decision-making processes.

Matthew Beighley (01:51):

How does climate affect indigenous communities in a different way maybe than other communities?

Archana Soreng (01:59):

Indigenous peoples as I see, is we have been contributing to nature and contributing to protecting nature through our world view. For us, indigenous people, we are not mere part of nature. We are nature. Nature is a source of identity, culture, tradition, and language. Like my name is Archana Soreng. In my Kharia tribe, the meaning of my surname is rock. So we have indigenous communities all over the globe who also resonate that the element of nature is in the name as well. And this is one of my interaction I had with a friend of mine from Latin America who said, “Oh, it’s in our community as well.” So indigenous people have this world view where they do not see nature as a commercial commodity, unlike other people. So for us, nature is our identity.

(03:09):

The second thing which I feel how indigenous people are contributing to climate is that the way of living. Indigenous people have been engaging in eco-friendly way of living, sustainable way of living. Like for me, my community, if I say I have seen my grandfather, I have seen my elders using bottles made out of the bottle guard, pumpkin as vegetables, which the pulp is eaten and the outer crust is used as a water bottle, which is dried up. And we have leaf plates being made from leaves to eat it. And we also have this beds, and we also have small setting arrangements made out of the leaves of the date trees.

(04:01):

So there’s this entire thing of how we see, if we see plastic pollution as one of the major issues in this contemporary, then we also see that indigenous people have been having this eco-friendly way of living since ages. And that is why I feel when they are contributing or when we see that how they’re contributing, it’s also in terms of what they have been doing for generation altogether.

(04:30):

And then the third aspect, which I feel like how indigenous people are contributing to climate action is in terms of their community led practices, community led forest practices, community led forest conservation, biodiversity conservation practices, because they have institutions and governance mechanism on ground in their villages where they are coming together making collective decision of how will we protect our forest. There has been initiatives in a lot of regions where I come from and also across globe where there is forest patrolling, the communities are doing to protect the forest. They’re preventing from the timber mart fears and they are doing it in a very communitarian approach.

(05:19):

So it also comes down to institutions and governance of how they are doing. And this is of what I spoke about, how they are contributing. I would say that if I had to say this is in one particular line, what indigenous people are doing in terms of climate, they have been defending the nature, protecting the forest, and the nature, and the territories, their world view. And what makes them more special or how they are contributing is also this data, which very rightly says that 80% of the world biodiversity is protected by indigenous people when they compromise of less than 5% of the world’s population.

(06:00):

And how they are being impacted, I think it’s really important to see that how climate crisis is impacting indigenous people differently, which is in terms of cyclones, heat waves, unseasonal rainfalls. I would like to share a very small instances. I come from a forested areas and land. So when there is cyclones and floods, we often see that how the loss and damage is happening in the coastal areas, but barely do we see that how that rain, which is unseasonal rains coming and impacting the indigenous people in the forested area, which is pushing them to debt, migration, displacement, because of loss of agriculture products, because of impacts of climate crisis. And also this is what makes me realize that there are issues how people are being impacted from different groups and that needs to be highlighted.

Matthew Beighley (07:06):

What are you up against? What are the obstacles that you have?

Archana Soreng (07:10):

I think one of the key obstacles is people fail to see the perspective of indigenous people in the climate discourse.

(07:20):

And the other aspect which I would like to highlight is representation in itself. I would like to share it from my journey. When I was in my initial days, one of my first UN conferences, I had been to it, which was on land. And I saw it was in my country. And I saw barely there was any indigenous people or tribal communities in the meeting, which is not only the case there, but I have been to different conferences and meetings on climate where we do barely have indigenous young people in those spaces. And if I say so, from Asia or global south. And that is why I feel that when the people itself are not there, how will the laws and policies will be taking them into consideration? So I would say that we need huge amount of participation of indigenous people, indigenous youth, the voices being there.

(08:26):

And the other thing which I feel is really important is in terms of recognizing the role of indigenous people, and recognizing their rights, and enforcing their rights, rights over the land, forests, and territories, and respecting their culture, tradition, language is super important in terms of the climate dynamics. It’s only in the latest or recent IBCC report, which is the climate report which everyone accepted, is they saw that rights of indigenous people is being seen and that knowledge is being seen as one of the critical ways of climate action. So I feel it’s really important also to see rights of indigenous people as an important way of engaging in terms of climate solutions.

Matthew Beighley (09:15):

Is there something in your own life, in your own experience that led you on the path to do this work? A moment maybe, or?

Archana Soreng (09:23):

Yeah, I think it’s been a whole journey in itself because I feel one of the key thing which led me to be here is because of my grandfather, and my family in itself, is my grandfather was a pioneer of community-led forest protection practices in my village. So they brought together villagers and community members from their village, from our village and across the village in terms of protecting the forest we share.

(09:54):

And that is something which I feel has led to my family in itself. And my father and my mother both were of the opinion that if you really want to contribute back to the community, you have to engage into policymaking. and I felt this is so important. Unlike, when they said it, I was not able to hold it well. But when I was in my graduation, I had the opportunity of going to communities and visiting communities and then I was like, “Oh, the communities are living the same eco-friendly way of living. The tribal community, as in my community, they’re facing the same challenges as in my communities. And what is supersedes them is an umbrella approach, is the law. The law made for us will be implemented in my community and also in their communities. And that is what I felt that there was this thing of laws are being implemented on us, but it’s not we who are being able to make the law or being able to access those.

(11:11):

But there’s also most important turning point I would say in this entire journey is when I was in my masters and we had environmental regulation as a subject. And I was like, all the things I’m reading in the curriculum is what I have seen it in my village, like eco-friendly way of living, forest conservation, and all of the perspective. And there was this reflection and insight that these literatures have not been written by my community but have been written by someone else. And that made me realize that I have this access to education, and it is because of the struggles and sacrifice of my community members and elders. And I want to write my own history, my own culture, and advocate for our perspective.

(12:03):

It was only then I lost my father and that made me realize that how do I write it? Because that made me realize that our elders will no longer be with us and we need to go back to our communities. We need to go back to our roots, embrace our roots because we as a generation are the bridge between the current indigenous tribal leaders and also upcoming generation. And that led me to go back to my community advocate and understand about the nuances. And that was a journey where I was able to get an opportunity to reflect on how rights of indigenous people, tribal communities, Adivasi communities on right to land, forest is related with climate change and climate justice, which makes me now confident to say, is that land rights issue is a climate justice issue, forest rights issue is a climate justice issue. And we need to see it from that lens.

(13:10):

And that is what led me to advocating in this space. And that is what led me to accessing different spaces and also engaging in UN spaces. And that led me to be a member and part of UN Secretary General’s Youth Advisory group on climate change. I was part of the first cohort from 2020 to 2023. It was an immense big opportunity for me to be part of the United Nations and to be with the leadership there.

(13:43):

And I think one of the amazing experience or my learning in this entire UN journey is we need more leaders who are being able and have the intention to listen from young people and act upon it, because we see that those spaces are not there and are shrinking. And we also feel like it’s really important to make sure that there is meaningful leadership of young people across the levels of decision making from drafting to the implementation processes.

(14:26):

And most importantly, what resonates from this entire journey is also how you can make difference. Because I have seen in that entire journey that how my narrative or me advocating for indigenous communities have made changes in that ecosystem. Because in that journey you find your allies, you find your people, your community, and build solidarity, and get strength from across the peoples, but most importantly also from indigenous communities across the globe.

(15:09):

And there is one thing which I still remember is speak truth to power. And that I feel is so important. And it has very different connotations for me. I understand that there is no safe and enabling spaces for young people to speak truth to power. And I feel in order to speak truth to power to make changes, there’s a need to make safe and enabling spaces for young people.

(15:41):

I would also share about how one of the things stuck with me in one of my interaction with Deputy Secretary General was in our first meeting when she said that, “Never ever forget your roots and your people, where you come from.” And I feel that is something which is so important for us to hold onto and advocate when we are seeing it from a lens of climate perspective, like who I am, where I come, because every communities is facing issues and challenges in a very different way. And that is what also led me that there’s barely any resources for indigenous communities, local communities, and young people to engage in this process.

(16:25):

So we did a study on climate philanthropy and we found that only 2%, out of the 2% of the climate philanthropy, 0.75% is going to young people, and that to mostly in the global north. And that is barely reaching out to young people in the global south. And that’s why we curated an initiative called Youth Climate Justice Fund, where we are trying to re-grant money to young people and reach out to them. So there’s a need of resource allocation to young people around it.

(17:07):

So I would say that my entire journey started off from my individual personal experience from my family, and that led to an intention to contribute back to the community, which led me to be in different spaces of public policy and advocacy. And then now I am in a space where I am engaging in philanthropy to engage to how do we mobilize resources to young people. And with other heart, which I would say is I am currently working with the global coalition of indigenous people, and local communities, and Afro descendants currently working as Asia youth lead. And I feel it’s really important for us to also see that how do we create more enabling spaces of supporting and encouraging young people.

Matthew Beighley (18:02):

What’s your vision? What’s the world you’d like to see?

Archana Soreng (18:07):

I would see a world or a vision for the world is to be filled with love. And when I say to be filled with love, is like I feel love can move and change dynamics because we are lacking out on love, respect, and solidarity. We need love to be able to work for our people. We need love to be able to work for earth and the world. We need love to take care of ourselves as well. So I would vision that our world is rooted with love and justice.

(18:58):

And with the work which I have been doing, I would see more and more indigenous people and young people being able to be seated in decision making spaces, rights of indigenous people over the land, forests, and territories are recognized and enforced, and more resources are being allocated to indigenous people and local communities, but most importantly, they’re also having the ownership over that.

Host (intro):

Welcome to Role Models for Change, a series of conversations with social entrepreneurs and other innovators working on the front lines of some of the world’s most pressing problems.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Hello, Nathan, and thank you so much for joining us today at the Skoll World Forum. Really excited to speak to you today. I guess to begin with, can you just introduce yourselves to us and explain a little bit about the work that you’re doing?

Nathan Méténier:

I’m Nathan, I’m a climate and LGBTQI2S+ activist. I have been working on climate and climate justice, environmental justice and climate issues for about 10 years now. And I’m here at the Skoll Forum representing a collective called the Youth Climate Justice Fund.

And we are a movement-led, youth-led participative fund supporting young people, next generation, young leaders fighting for the climate crisis. Fighting for environmental protection and social justice everywhere. And in the past, I’ve been a youth advisor to the UN Secretary General. And also have funded an organization called Generation Climate Europe, which is a coalition of some of the major youth movements in Europe. And also been part of various different other youth movements in Europe of other years.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

And I suppose, how did you first begin? At what age did you first take an interest in this? And I suppose, when did that turn into the work aspect as well?

Nathan Méténier:

Yeah, I grew up as a queer kid and therefore always felt a little bit different. And growing up in a pretty rural area in a village in the Alps, I was always amazed by the beauty of nature and the beauty of our nature environment. But at the same time, very early on I noticed the effect of the climate crisis on the mountains, on the use of water, on the issues around farming and different other elements.

And that sort of felt really right. And I was always really strike how at the European Union decision-making processes, we would always talk about climate crisis as something that is far away and that only happens in countries that are the most impacted. But of course at home, it is a reality and we already have millions of climate migrants.

And so that triggered my activism to be involved on those issues. And then obviously, also working on queer issues. I really sort of connecting those two issues together and that sort of nourished and empowered my intersectional activism.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Yeah, brilliant. And I suppose then from your perspective, what exactly is the problem that you’re trying to solve? Well, historically and well ongoing, I suppose the lack of youth voices and perhaps more broadly the diversity involved in those conversations.

Nathan Méténier:

When I joined as a youth advisor to the UN Secretary General, of course it was the COVID pandemic. So we obviously were not looking just at climate, but issues of just transition. At the time, we were talking a lot about building back better and different other elements that were really important around especially just transition.

We realized that no matter where we would talk to and consult with young people on ocean issues, on conservation, on biodiversity, on energy, always, and again and again, what would come back is the lack of funding, the lack of resources so that groups on the ground can do their work. And so we designed a study and interviewed dozens of young people around the world, looked at the data.

And we found that only 0.76% of most of the climate funding would go to youth movements. Despite the incredible power and the incredible work that youth climate movements have been able to do since 2018. Even before that, but especially in 2018 when we played such an essential role in the European Green Deal in Europe, for example. But also most recently the Inflation Reduction Act in the US.

And that felt like we needed to create something that could help philanthropic investments to be channeled to incredible next generation young leadership. Especially young leaders who are part of communities that have been historically marginalized against. And here we think about queer young people, Indigenous, Native, and local communities. We think also about people of colors and any ethnic communities that have been ignored for many years and underfunded.

And yet very often those communities are doing essential role to push for just transition, to push for social justice on the ground, and making sure that there is implementation, right? Because we have really strong international commitments that are binding or not. And yet we see that their progress is lacking.

And the diversity and equity dimension is really essential because we see at the same time that these dynamics are happening, that also populism is rising. And we really need to make sure that politics, and also young people coming from diverse communities, are represented in places of power and can also be part of those decisions.

And so that is what we do at the Youth Climate Justice Fund. We fund, resource, support young leaders. We trust them, meaning that if an initiative is non-registered, but led by really lovely, amazing community-rooted young leaders at the grassroots level, that are driven by community priorities, we invest in them with funding, capacity development. And also connecting them to different initiatives so that they can really thrive and do their work.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Yeah, that sounds like really inspiring progress that you’ve been making. I just wonder, do you have any particular examples of some of those leaders that you mentioned? Those young leaders that are kind of trailblazing the way that you think that are inspiring?

Nathan Méténier:

Yeah. I’m particularly inspired by some of our grantee partners. For example, we support the Africa Youth Pastoralist Network, which is an incredible network in Africa that is really sort of bringing that dimension and the work that pastoralists are doing on the ground.

We also support initiatives that are trying to mobilize young people in the lead up to essential international conference. For the first time in a very long time, a COP is going to happen in Brazil. And so it’s so important that young people from Latin America, from Brazil, especially those coming from marginalized communities, can really be part of the agenda, decision making, and the planning of that conference.

I think also about incredible groups that are working in countries such as Indonesia, South Africa, Mexico. That are also really important countries when it comes to climate. And really trying to shift narratives and to bring different voices.

So we also support, for example, woman-led groups that are trying to change how climate is being talked about and represented in mainstream media. And all those different voices I think are essential to create more pressure. But also an essential thing, which is bringing everyone in this fight against the climate crisis.

It shouldn’t be something that is just run and decided by people in the north, people that are often white. And so that’s what we’re trying through our funding. And we do it in a way that is movement-led, and we use participative grantmaking. Because participative grantmaking is an incredible opportunity to make sure that we create trust not as an outcome, but as a process.

And through that, we’re able to work with our grantee partners that feel they can really share with us their vulnerabilities. Share with us what’s really happening on the ground because that is helping us to understand what’s our impact? And what’s the impact of the work and the resources that we’re providing to them? And so that is a very exciting thing in the way we do things and the way we try to change philanthropy.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

And I suppose, could you just explain for those who might not necessarily know how that works, what exactly is participative grantmaking? I suppose, in improving the process of making it more sort of democratic?

Nathan Méténier:

Yeah, I think there’s various ways to do it. The way we do it is that the entire fund is led by young people who have been part or are still part of youth movements. So our steering committee members are incredible young leaders from all around the world, and they are part of the decision of where the funding should go.

We also have regional leads in different regions who scout project and support young people to apply. So for example, when youth groups apply to the Youth Climate Justice Fund, they can apply in more than seven languages. And we really try to make sure that the application process is as simple and as accessible as possible. Because that again, has been a barrier for years for many groups to really access funding and to have resources for the incredible work that they’re doing. And then once this is done, we go through basic eligibility criteria and different sets of review that are all made by different young leaders.

And we are also starting a decentralization of our participative grantmaking, meaning that decisions will be happening at the regional level. Because obviously what is so essential is to make sure that regions and countries can also decide for their own priorities. Because the issues that are happening in Latin America might be similar and relative to other regions, but they might be also very different to others.

And so participative grantmaking think is such an incredible, empowering way. In a way that when a founder invests in the Youth Climate Justice Fund, the moment that conversation starts, it’s already empowering young people because everyone are young leaders in the fund. And I think this is such a beautiful thing when you think about the power of intermediary and the power of organization or donor collaborative, that bring founders to learn about issues. What’s so exciting about us is that it’s all youth-led. So the impact is everywhere all the time, and that is something I’m super happy about.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Right, yeah, it seems like it’s really baked into the system already, as you say. I just suppose from, you mentioned before obviously working for the UN Secretary General António Guterres. And I just wondered, can you speak a bit about what that experience was like? Obviously it’s quite a pioneering sort of position to have, and what exactly did you learn from that?

Nathan Méténier:

So in 2020, the UN Secretary General started an advisory council of seven young leaders from all around the world. To advise him on his work around climate issues, environmental issues, and more generally how to recover from the world biggest pandemic, the world biggest health situation.

And it was an incredible learning to also see the power that young people can have when there is a formal seat at the table. We would meet with them regularly. We’ve met with him several time in person, and I wouldn’t say that this is everything. Obviously this is not the end, you get a seat on the table and then.

But that really helped us not only to have a tremendous influence on him, to make sure that not only he would focus on issues of climate mitigation, climate finance. But also really paying attention to the question of loss and damage, for example, where young movements have played an essential role in getting the funds starting at the last climate conference. But also making sure that the UN Secretary General would connect the different portfolio that he is working on.

So we’ve really spent a lot of work, and for example, my colleague Archana, who’s also a school fellow, played an essential role in showcasing the incredible work that Indigenous people are. And that played a really big influence on the UN Secretary General to really champion even more that agenda.

And I think this is also true for many other youth-led advisory boards because right now we do have several countries that have started their advisory boards. We also have a couple of companies. And that is really helpful to empower also young people to understand how processes are done.

Because sadly, the climate crisis is such that we need to make sure to invest so much in young people right now. So that they are ready to make the decision that often will be even more difficult than in the past, given the rapidity and the harshness of the climate crisis right now.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

And in terms of the fund itself, obviously you said that the system is really something quite new and innovative. And I just wonder, do you know the figures to mind in terms of how many grants have now actually been given roughly? And what kind of sums have already been granted?

Nathan Méténier:

Yeah, I mean, it’s something that I always feels a little bit tickled and really excited about when I get asked this question. We have funded 40 incredible youth-led initiatives in 24 countries in 2023, for half a million dollar. And this year we will be able to triple that commitment. And of course there is so much more that’s needed.

When we did the Youth Climate Justice Study, we realized that there was a need for an additional at least 15 million per year based on needs that we had identified at the time. Of course, now two years after, the needs have increased. There’s even more enthusiasm and power and motivation to work on youth-led initiatives that are tackling not only the climate crisis, but also environmental protection and social justice.

So we need to do much more. But the Youth Climate Justice Fund is definitely a new player in that field. Not only to support young people and make sure that we can work with philanthropies to invest in a powerful and enthusiastic way in youth movements all around the world, but also to provide youth to youth capacity development, which is essential.

Yes, funding is essential and really important, but supporting young people to know how to run an organization, how to do administration, how to do financial management, how to manage volunteers. This is really important too, and especially because we work with a lot of unregistered groups that are just starting or have an incredible ID that is really essential.

So the youth-to-youth capacity development is really important, but also donor-influencing. And so the work that we do with the Youth Climate Justice Fund is really also to gather some of the largest philanthropies and also new donors. To really sort of have conversation about impact, evidence, providing stories of incredible youth groups.

And that already, that advising work, that influencing work, is already creating a phenomenon where philanthropies are like, “Hey, I can also potentially invest myself in youth movement.” And then we provide free advising to philanthropies in case they want to invest more in youth movements in sharing best practices. Unrestricted funding, multi-year funding.

If you’re working with the youth groups, you might want to be even more kind and compassionate because these are young people who might be doing their first initiative, and yet it might be the most powerful grantee that you have in your portfolio. So we really try to work with different philanthropic institutions to also encourage them to fund directly youth movements. To really grow the pie, which is the goal, to get to a more abundant ecosystem where really youth movements can thrive in the work they do.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

And I suppose obviously you gave the examples of the number of projects that are being done and the amount of money that’s successfully been invested. But I just wonder how exactly do you decide if this is working? How do you measure the impact or the success? By what metrics do you really look at? To think, obviously there’s the money side of things as well, but in your mind, how do you assess whether this is achieving what you want to achieve?

Nathan Méténier:

The incredible opportunity that participative grantmaking offers is an opportunity to create understanding with the grantee partners and the people that are stewarding the fund. So in the Youth Climate Justice Fund, of course, we are very transparent about the way decisions are made. People know how the process works, everything is on our website.

But at the same time, the youth to youth capacity development, which means capacity development happens everywhere, and there are incredible organization that are specialized in doing it. But very often what we found is that it is offered by organization in the Global North to organizations in the Global South. Or to organizations that are working with communities that are marginalized in the Global North as well.

And what came up of our study was that youth movements were saying, “Why don’t we have organization that look like us? That are from our regions? Being able to understand what’s happening in our own lives to help us to do our work?”

And so we thought that it was so important to create a model that would be able to be regionalized, contextualized. So that when young people are reaching out to one of the members of the Youth Climate Justice Fund, any questions they may have, they find themselves speaking to a former youth activist. Or someone who’s set up an organization in the past. Or even ideally, someone who’s from their own region and can talk in their own language.

Of course, this is not possible always because there’s so many countries. But already being able to talk in Swahili and Spanish, in French and Arabic, that’s already really, really meaningful to be able to support grantee partners. And that is the opportunity to measure and evaluate the work we do.

Because through that trusted model that is allowed through the participative grantmaking, but also through the youth-to-youth capacity development, the goal is that grantee partners then feel able to be vulnerable with us and to say, “Hey, this is the issue I’m having. I am not managing to get access to that policymaker, which was key to our decision.”

Or, “I’m not able to have as much conservation in this area because this external factor happen.” And that is really what we’re trying to get with the Youth Climate Justice Fund, is to really say, “We want you to be open and transparent about your issues because we’re here to support you.”

And maybe we can connect you to some partners that can support you. Maybe we have someone in our network that has went through this challenge and can support you. Because sadly, again and again, we see such a huge difference between the impact that is being reported and the reality of what’s happening on the ground.

And our opinion is because when you are working in a nonprofit, and many of us have been grantee partners that have worked for many years with different foundations, you are very scared to say the truth about what’s happening in your work and when you don’t succeed to do something because you might lose the funding. And so what we are really trying to do, and of course we are learning every day, is to create a model where we don’t get that.

Where we really know what’s happening on the ground, and if something doesn’t work, that’s okay. That’s our responsibility to see the amazing opportunities. And if some things don’t work, that is a learning not just for the Youth Climate Justice Fund, it is also a learning for the entire youth movements. And more so for the entire social sector. That philanthropists can also learn from, other nonprofits, international organizations.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Yeah, that’s a really, really interesting model to have there. And I just wonder as well, when it comes to what you’re speaking quite honestly about the emotions and the fear that grantees might have if things aren’t going well.

But I just wonder as well, if there are some, I suppose, well, young people out there that are interested in doing more work, whether it’s activism or working on projects like this, but they’re still very much at the beginning of that pipeline. I mean, what advice would you give to them? What would you have to say to them? Do you have any words of encouragement?

Nathan Méténier:

Yeah, I mean, I love the word pipeline first because I think that’s exactly what we’re doing. We are creating a pipeline of incredible community-rooted young leaders that are hopefully ego-less, driven by community priorities, to then run some of the most successful campaigns, initiatives, projects, activism, movements. And that is really the business we’re in.

I think if I had one advice to give is remaining curious. Yes, there is not enough funding and not enough resources that are going to young people, which is an increasing part of the world and probably the biggest renewable energy that we have to tackle the climate crisis. But at the same time, remaining curious and being open about researching for opportunities.

Frankly, the Youth Climate Justice Fund only takes to Google online. Hopefully this is one of the first thing that would come up. And then you can apply. We have an open call happening every year. Everyone under 35 that is running an amazing project on climate justice, environmental protection, social issues can apply and have the chance to get it.

And I think this is already really exciting for a lot of young people. And also future young people that are getting in this space wondering what to do, to start their project and do potentially an incredible work.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

I suppose just one last question for you then, Nathan, is just to do with, I’d be interested to know what exactly… Well, obviously there’s the climate crisis is very much pressing, so this isn’t a case of working to long timelines. But what exactly is it that you’re working towards? Can you just describe to us and paint the picture a bit of what a world where ideally things are as they should be when it comes to youth voices?

Nathan Méténier:

Our theory of change is that we are not able to make progress on climate outcomes because we haven’t paid enough attention to the social justice component of the climate crisis. And we have continuously continued to push for better policies around climate action without making sure that these would be redistributed, especially to those that will be the most impacted by the climate crisis.

But also the green transition. When you think about workers, young people who are based in communities that are heavily dependent on the fossil fuel industry. And so to get to a world that is not only greener but also fairer, we think that is essential to harness the power of young people to hold policy makers accountable on their promises.

Meaning that in the past 10 years, there’s been a lot of promises from the Paris Agreement at COP21 to now, on getting really bold action on the climate crisis and social justice. We’re yet to see that. And we’ve seen of course, pushback and we’ve seen politicians backing track, especially, for example, in this country, the United Kingdom.

The second objective that we’re working on is to make sure that when there is momentum and that we’re managing to push for really strong climate or environmental or just transition policy, there is a really strong equitable component to it. And a good example of that, even if it’s not enough, is the Inflation Reduction Act, which really had a good component around equity and just transition. Even though that was so small compared to the amount that was given to green or renewable energy initiatives.

And the third component we’re working on is to make sure that we are really empowering the next generation of incredible community-rooted young leaders, to really do that work and do all these different issues that we’re trying to make sure to address.

Peter Yeung (interviewer):

Yeah. Well, thank you so much for your time there, Nathan.

Nathan Méténier:

Cool. Thanks.

Related Content