Role Models for Change

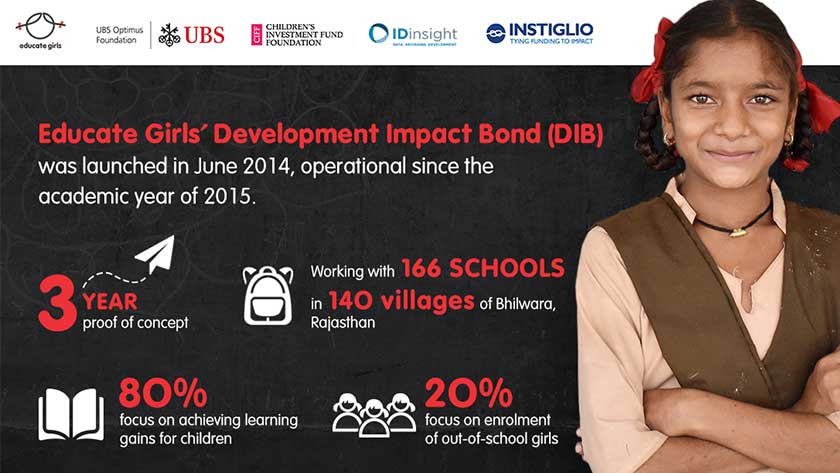

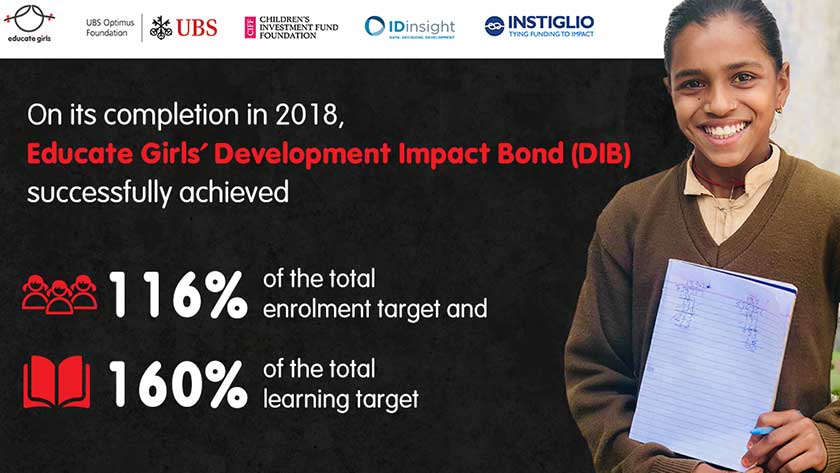

Educate Girls, an Indian NGO working to enroll out-of-school girls and increase learning for girls and boys, recently reached a major milestone: completion of the world’s first Development Impact Bond (DIB) in education. At the end of three years, Educate Girls’ results in Rajasthan exceeded the DIB’s goals, highlighting the effectiveness of their approach to both increased enrollment and learning outcomes.

Analysis from the Brookings Institute, which closely followed this proof-of-concept DIB over the full three years, concluded that while the Educate Girls’ interventions were a clear success, “the field still lacks rigorous evidence comparing the DIB financing mechanism to other ways of paying for social services.” IDinsight, serving as the independent evaluator, prepared a full report [PDF] on the results. We chatted with Alison Bukhari and Maharshi Vaishnav from Educate Girls to get a better sense of how the DIB process shaped their approach to fundamentally shift gender inequality in education.

Included below is also an audio feature—an intimate conversation between Safeena Husain, Founder and Executive Director of Educate Girls, and James Nardella, Principal at the Skoll Foundation.

Zach Slobig: We checked in last year for the first year results of the three-year bond. At that point Educate Girls had reached nearly 88 percent of the enrollment target and 50 percent of the 3-year learning target in three remote, rural blocks in Bhilwara, Rajasthan, India. These results are impressive! Help us understand the tremendous progress in learning in this final year.

Alison Bukhari and Maharshi Vaishnav: It’s rewarding and unexpected that in the final year of the DIB, children’s learning moved 79 percent more than the children in comparable schools, not on our program. That is almost the equivalent of an additional year in education. We moved from an average of about 1,400 learning gains in years one and two, to nearly 6,000 in the final year.

We are convinced that the results are a combination of three factors:

We are normally subjected to quite short-term funding and must renew grant agreements on an annual basis. It is hard to deliver meaningful outcomes in this short time frame. Often, we are left reporting against our activities and some basic outputs over a year. With the DIB we were able to secure three years-worth of funding, but even this is not enough in a program that includes innovation and adaptive management, particularly in the education sector.

Year one we could categorize as a ‘start-up’ and learning year, when we realised clearly the shortcomings of our curriculum and took the decision to revamp it with new pedagogy experts Sol’s Ark. In year two we tested and refined the new curriculum. We only really hit our stride in year three when we reaped the fruits of the earlier hard work and data analysis. The children who were in the program for the full three years achieved the greatest learning gains. We learned that a DIB needs more start-up time and we confirmed that education outcomes compound over time.

Zach: Tell us about some of the corrective measures you took after the 2-year results. How does your child-centric curriculum differ from traditional learning approaches in the area?

Alison and Maharshi: At the outset of year three, the classroom was divided into groups by learning level rather than by age or grade so that teachers would focus more on the children struggling the most.

At the end of year one, we engaged with a pedagogy expert and totally revamped the curriculum. We piloted a new curriculum called Gyan ka Pitara or ‘repository of knowledge’ across 19 villages and then across the full DIB treatment schools. This new curriculum was more child-centric, gender sensitive and included many more teaching aids for the Educate Girls staff and volunteers and many more worksheets and games for the children. Not all children learn through the same exercise, at the same time or in the same way.

We conducted widespread classroom observations to inform the curriculum design. Really understanding what the children were getting wrong—error analysis—helped us address the gaps in their knowledge. For children who were chronically absent, field teams conducted catch up lessons at home.

Zach: What lessons are worth sharing around how you approached outreach for hard-to-enroll girls? Can you tell us a single brief story of how Team Balika (community outreach volunteers) is effective in influencing community mindset around girls’ education?

Alison and Maharshi: Enrolling the older girls is a particular challenge, as there are often a number of people who hold influence over whether a girl goes to school or not. One 10-year old girl called Sandhya, who had not been to school before, was eventually enrolled but still had very irregular attendance. First, the grandmother had to be convinced, because Sandhya looked after her grandmother while her parents worked in the fields. Next, the Educate Girls team had to persuade the parents. Lastly, Sandhya herself needed inspiration. We brought together a group of girls from Sandhya’s class to explain to her how much they enjoyed school, and what they were now learning. Often Educate Girls works with the School Management Committee in the village—a group of parents that uses peer support to persuade parents to enroll their chronically absent children.

A one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate. To change a community’s mindset, you must work at multiple levels, have tenacity, and draw on field staff from multiple locations to test different approaches constantly. At the individual level, we aim to enroll every single out-of-school girl. At the community level, we aim to shift the whole mindset of the village towards protecting and promoting gender equality.

Zach: This experience seems like a powerful proof of concept—Educate Girls is very much at the forefront of this novel approach to funding. The reach of this initiative, relatively speaking, was very small-scale. What will it take for DIBs to become mainstream?

Alison and Maharshi: We think a better question is should DIBs become mainstream. We have yet to demonstrate value for money and scale. Hence their replicability is not yet determined. Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are another matter. With SIBs, the government pays for the outcomes and that has a high potential for mainstreaming. DIBs still must prove their value beyond the lab approach for promising practice.

We think a new approach to grantmaking should be mainstreamed, and this DIB proof-of-concept shows clearly that an outcomes focus and multi-year, flexible funding can enhance an NGO’s ability to deliver better results.

Zach: What, if anything, would you do differently if this opportunity presented itself again?

Alison and Maharshi: We would have aimed for a larger scale to ensure that the evaluation offered the best value for money. We would have included a pre-implementation phase of 6-9 months for a baseline, developing the performance management system, and training staff.

Back in 2014, there wasn’t the right environment to engage the government in a better way—now we would seek deeper engagement with the State Education Ministry to ensure that any future DIB is a precursor to the government paying for outcomes. We would have also included a budget line for course correction, adaptive management, and more importantly innovation.

Zach: How might DIBs fit into the puzzle pieces of funding required to meet the SDGs?

Alison and Maharshi: To meet the SDGs, governments must play a critical role in funding and scaling interventions. Given that we need over $2 trillion to accomplish all SDGs, it could make sense if the risk is borne by the private sector as investors and the governments play the role of underwriters or outcome payers.

The primary role of the Development Impact Bond is to incubate promising programs, test them, and ready them to scale up. DIBs could be a pathway to engage the government as the outcome funder, though they may not become a commonplace funding instrument.

Notifications