Centered Self: Systems Change from the Inside Out

I lay back in the ambulance early in the morning as it rushed through the dark streets of London. In those days there were no sirens but instead there was an electronic bell. Now I am 71, but then I was 12, hospitalised, to all intents and purposes, with an acute appendicitis. We arrived at the hospital and the surgeon swept up to me in emergency and very gently palpated my tummy. I was in immense pain, but it was not so site specific. I was admitted for observation but not to the theatre.

To this day I still have my appendix, so what had just happened? As I understand it now, I was suffering from psychosomatic pain. In lay terms I was suffering genuine pain derived from stress. I was having a child’s version of a nervous breakdown. I lay back and watched the ceiling pass over my head as I was wheeled to safety. I slept and slept and awoke to the quiet noise of a breathing pump gently working somewhere in the background.

My father and mother were separated when I was five. Shirley, my mum, and Malcolm, my stepdad, lived in Corsica, working as artists. A writer and painter, respectively. They were always broke and very unsure about how to get me schooled. My actual dad, Tony, offered to have me live with him in London so that I could access an English school. In time I was sent on the train right across France and the Channel, arriving at Victoria Station on the boat train. I do not recall any of the goodbyes. No one met me at Victoria and eventually the police delivered me to the address in North London where my dad, also working as an artist, lived with his wife, Terry.

Neither Tony nor my mother, Shirley, had communicated with Terry about my imminent arrival and that I would be staying for a long period of time. The row that ensued can only be imagined. In time I did start school but found it hard to adapt. Food at my new home was erratic and I found myself looking for food in the neighbourhood. Late at night I would steal out of the little box room that had been hastily put together for me, walk through the city and end up at the one home that made me welcome. The home of Ray and Ronnie, now both dead, and their son Andy, now my oldest friend.

I had gone from being part of a family with two younger brothers with lots of bowls of pasta and risotto with fresh fish and salad to pretty much no food and my own company spent mostly in the little box room. Back in the hospital I awoke to the sound of an air pump. I got out of bed and walked towards the machine emitting this wheezing sound.

Through a porthole I saw a little face looking up at me. The machine was an old fashioned “iron lung” and the gentleman inside was a miner whose lungs had given out and the machine was breathing for him. The only “medicine” he received was a bottle of Guinness a day. This he asked me to administer to him via some sort of little hose pipe. I felt strangely empowered—this was after all something I could do—and after a time a nurse bustled in and took in the scene. A child with wild dirty hair drip-feeding a man in an iron lung with beer.

She ran a bath for my first proper wash in a long time and the next day a barber arrived. We two inhabitants of the tiny ward went to sleep early. I ate my food with enthusiasm and my weight loss corrected slowly. I now realise that behind the scenes a whole machinery had ground into gear involving Ray and Ronnie, the authorities, and, finally, my mother and stepfather. Each night I would get snuggled down in the old well darned national health service sheets and the nurse would reach over and kiss me on the cheek good night. She smelled a little of honey and its faint odour is as vivid to me today as it was then—it spelt the words safety and love. Looking back, I now realise that she, at times, wore her uniform and, at times, she was in her own clothes. She came every night to reassure me regardless of her own evening roster or private agenda.

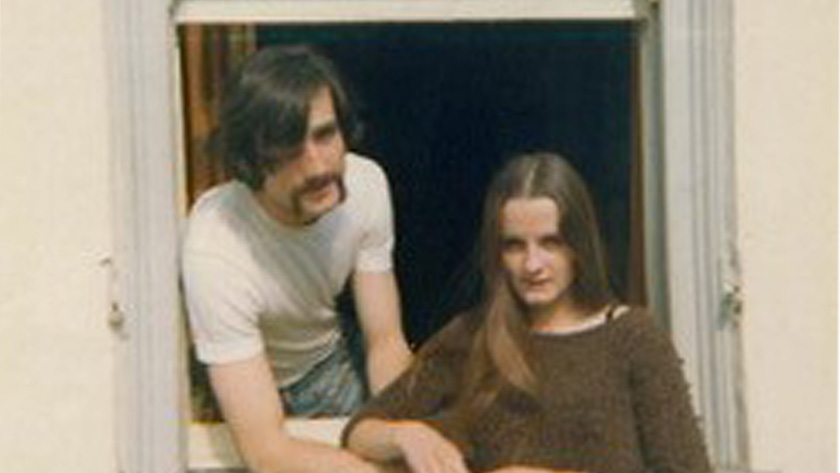

The author as a teenager in Corsica

The author as a teenager in Corsica

I left London soon afterwards and never returned to the house of my father. My mother never really forgave herself at the trauma that I had suffered. I swam off the rocks in Calvi, Corsica, and dove with a local sub-aqua club–in time teaching folk how to dive themselves. Hanging on to the metaphor for a moment longer, I took a long time to swim to the surface. But it was at this time as I recuperated that I now realise that moved me from being a “glass half empty” person to one whose glass was “half full”. I had survived, more than that, I had coped well as a child and now something momentous was about to happen. Through the strangest of circumstances, I was about to receive a massive boost to my life chances and I reached out and grasped the offer with both hands.

At that time, an elderly couple of gentlemen would come to Corsica for their summer holidays. They became firm friends of Shirley and Malcolm. Stanley, the Englishman of the couple, was a theatre impresario and at a certain moment he went to Paris. Algeria was ceding from France, characterised by the struggles of the OAS/FLN–terrorism has always been with us. A “bombe plastique” detonated as Stanley was walking by and ripped away much of his face. It was a dreadful event and the French Government offered him a massive sum as compensation. He would recuperate in Corsica between operations and Shirley would fuss around him and I, in turn, would sit with him unfazed by his wounds. I felt that he would heal, and I never regarded his scars as disfiguring. Stanley knew of my difficult time in London and contacted Shirley. He made a gift of some of his compensation funds sufficient to pay for all my boarding school education up to the age of 18. He wanted to see something good come out of his awful experience. Suddenly, I had a future.

I attended Dartington Hall School in Devon. This incredible place was founded by a couple, Leonard Elmhirst and Dorothy Whitney Straight, an Englishman and an American woman each as remarkable as the other. It was a perfect school for me, founded as it was on the principle that you must take charge of your own self will. The school was co-ed and one day a new girl arrived. She was called Giselle. Within minutes of her arrival my friend Nick and I were flipping a coin to see who would ask her out first. He won and so with great resolution I cheated on him and snuck behind his back to ask Giselle out first! We have now been married 51 years and have three incredible children and six wonderful grandchildren.

In the early years of our marriage we travelled to Zambia as VSO volunteers and I also worked for the same outfit at HQ as their Agricultural Officer. We decided to have a family early and Tamar was soon born followed by Luke. Later still Jessica was to join the family and we were complete!

I studied Environmental Studies as a mature student and wrote about gardening for disabled people as my special subject for the degree. My lovely father-in-law, Theo, was a dedicated horticulturist and he took a great interest in this study. In 1977 I sat down with him to design and eventually launch what was to be my first social organisation. Some 40 years later, this organisation is called Thrive. In those early days, the design innovation was very much focused around the joy and creativity of working in a garden and experiencing the reduction of stress and anxiety that this process brought about.

We were able to demonstrate, with the scientific cooperation of medical staff, that mental health patients, whilst gardening, could expect to see their intake of pharmaceutical drugs gradually lower, whilst their overall resilience rose. Theo was able to mentor me, mostly by a wonderful form of active and encouraging listening, and, also, through his extensive network from which emerged the first Chair of Trustees and a future trustee who led us to my first major funding from the Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust.

Through Theo’s network the Director of the Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust invited me to write him a letter to outline the idea with a budget. Once again, I sat down with Theo, my dear father-in-law, and we chiselled out the letter and the budget. It is amazing to me, looking back, that I was able to propose the creation of a whole organisation over a three-year period for £70,000–what seemed like a huge amount of money in those days. In April 1978, a letter arrived, and Giselle and I sat in our kitchen looking at the envelope. We opened it and learnt with mounting excitement that the Trustees had agreed to the grant, but there was one problem—we hadn’t asked for quite enough money!

I can recall one of our earlier operations working with a large institution for people who used to be labelled “the mentally handicapped”. We formed a gardening crew and the young men became tanned as they worked outside their ward for the first time in many years. They lost weight, ate more, and were reducing their pharmaceutical drug intake. One of the youngsters asked me to come and meet with him and his parents who were visiting for the day. We went to the austere ward with the long row of beds and beside each bed, a locker. The locker was important since in a way it was the only personal space that a patient had.

His mum, dad and I all sat on the bed in a row and he stood in front of us. He said: “Mum, Dad, I have something for you”. He fished in the locker and produced a huge cabbage! He proudly stood and handed it over. “I grew this and now it is for you” he said. Through my tears of joy I felt so moved, so proud of him and of our work, and I could see healing in the act of giving and receiving which was so important to this family and tremendously satisfying for me. Here then, was a way of working that could bring healing not just to a few but to many thousands through engagement with the natural world.

Six years later in 1984 I found myself sitting with a group of disabled people in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, and they spoke with passion of the difficulties they had in creating independent lives away from the cloying “charity” extended to them at the time, and their own despair at disastrous underachievement due to lack of education and opportunity. Upon my return home our kitchen filled with conversation about these developments and observations and, with Giselle’s encouragement, I decided to propose an organisation which would work with disabled people in the developing world. So began a significant period of design, innovation and growth as I created Action on Disability and Development, which we launched in 1985.

The idea of disabled people having their own voice was still challenged by many rehabilitation organisations, medical facilities, and ministries of health. We proposed that at least fifty percent of the board be composed of disabled people. We exceeded this arrangement when it came to the staff, both at headquarters and overseas, since I strongly believe that representation is the most powerful way to support independence and liberation. We set about helping create disabled peoples’ organisations, first in Africa and then in India.

It was at this point that I met Joel Joffe. I had become a member of the Oxfam Board and he was being proposed as a Board member and so he got in touch. Joel was the co-founder of a successful insurance company called Allied Dunbar, but in a former life he had been the advocate for Nelson Mandela and his comrades during the Rivonia trials. He was an incredibly warm, kind man, and he took a great interest in the formation of ADD. He asked me to write a short paper and assemble a budget to start the organisation. I sent him the proposal then time went on.

“Well I think we got it,” he told me one day as we travelled to Oxfam with me at the wheel of his car. Allied Dunbar Charitable Trust had committed to funding ADD and in addition, he and his wife Vanetta would contribute their own money as well. I was so excited that I drove his car all over the road and only came back to my senses when somebody blew their horn at me.

Our programmes grew and we had a wonderful time backing the disability liberation movement as it developed, becoming ever more competent and confident. It was this sense of being heard, of being backed first by Stanley, then by Theo and now by Joel that kept my glass full to flowing over. After some ten years I wanted to run a big outfit and so gave in my notice and, in time, went to manage the organisation founded by Fritz Schumacher, the man who coined the phrase “Small is beautiful”. The Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG) is now called Practical Action.

Development organisations are often too eurocentric and I redesigned the management so that the executive board was composed of the heads of programme coming, as they did, from Peru, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, and so on. It was whilst I was sitting in my office at this formidable outfit that a man suddenly appeared and asked, “Have you got another outfit in you – that you wish to start?” Yes, as it happened, I did have.

I had travelled to the various offices of ITDG and, rather than take a day off, I went and met with people managing the mental health facilities of the country I was visiting. I was rocked back on my heels when I understood how small the resources were at the disposal of mentally ill people, how frightening their meagre facilities often were, and what a gap existed between the available treatment resources and the need. The need of the people themselves but also their families. We put ITDG through a change programme and after just under five years it was time to hand over to a new CEO. The mantra of “don’t stay too long” seemed to ring loud and true as did the belief that if I found a new niche that with backing I could go and explore that issue. I was indeed ready for another venture.

Nicholas Colloff represented a funder that specialised in start-ups and, in time, we took his trustees to India where they met mentally ill people and their families. After an immersion in the issue, I met with Nicholas and his trustees at a small hotel in Bangalore. They were astonished at the privation being felt by those that they met. We talked over the stories we had heard from the families visited. Of the dreams spoiled; the stigma felt so keenly. They became convinced of the need to fund this work and I was delighted to learn that they would fund the new organisation. I went to Joel Joffe and told him of my decision to leave ITDG and that I was minded to start this new outfit. After a little time, he told me that he would match the funds put forward by Nicholas and his trustees. We now had the funds to back the first development agency focused on mentally ill people in the developing world.

BasicNeeds, as it came to be known, grew fast in the early years, starting its first programme in India and then, later, in Ghana. We were blessed by a comradely welcome from the WHO that must have looked at our feisty little vessel bobbing alongside them with a fond regard. In time we started to grow our numbers and, by the time I left, some sixteen years later, we had served well over 800,000 folks in 15 countries. Our model has proven its impact and is now on TED which is satisfying. As we got started I recall walking in Accra and seeing a man in rags sitting on the pavement by a major crossing, the diesel fumes in his face. I sat next to him asking permission to sit down. After a while we talked. He was not vagrant, but he was lost to his family. As he talked, he taught me, all over again, to listen and then to take action.

In the end, I have created Thrive, ADD, and BasicNeeds, and co-created citiesRISE and, latterly, the Elders Council for Social Entrepreneurs. In between these outfits I have founded or co-founded other work that maybe I have chaired or handed on to other people to manage. Others tell me that I have used the same set of instincts that a commercial entrepreneur uses when starting her or his operation.

I have not rushed away from any of these outfits with unseemly haste, but I have certainly moved on regularly. In each case it has been easier to move on when I had something, some new idea, that I was going to accomplish next. At times, the shift between one outfit and another can appear restless, but it does not feel like this to me. Rather, it feels natural. I see it as spotting a need and then pulling together a band of people around an idea to execute an approach, or model, to meet that meet. It is the band of people that make the organisation a success and it is the leadership. To do this across cultures, ages, disabilities, and with the funds of those willing to give generously has been simply a lovely thing to do. Today, I have boiled this experience down and offer the knowledge back as a mentor and an advisor—a wonderful bonus.

What of that little lad who arrived on the boat train at Victoria Station? The lad in the ambulance heading to a psychosomatic diagnosis, the boy who had to search for food from bins, a wild haired emaciated child in the care of a man lying in an iron lung and a warm hearted, sensible, nurse who could see what was happening and did something about it?

Do I acknowledge the wound created in those early days of extremely poor parenting? Yes, I do. Always. Yet in the end I have made those experiences a driver for change and creativity. As a world shaping experience it would not have been enough without the strong support and validation created by Stanley, Theo, Nicholas, and Joel who found reason to believe in me and the ideas I have engendered. The love of Giselle and our adult kids now well into their forties is the final balm to the wound offering, as it does, solace and wisdom, but, best of all, gentle teasing that keeps my feet firmly on the ground.

Want more stories of transformational change on the world’s most pressing problems? Sign up for Skoll Foundation’s monthly newsletter.

Notifications